Antigen tests and "assurance testing" could help us return to near normal even before vaccines

Today's Managing Health Care Costs Number is $1

Much of the recent news in the US on the pandemic is troubling. It's depressing to read about clusters of infections at universities, athletes with severe COVID-related heart inflammation, continued shortage of tests in hard-hit states and the inexplicable culture war over face coverings.

But there is also some bright news.

On the vaccine front there are around 200 different vaccines under development. 31 are in clinical trials, and 8 are in the all-important Phase 3 (efficacy) trials. There are two vaccines currently approved for non-research use, one a Russian vaccine that has not undergone Phase 3 trials, and another being administered to Chinese army volunteers.

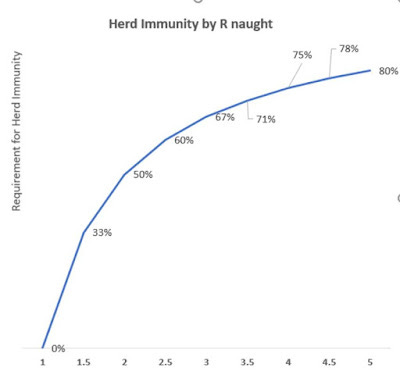

I think that even if there is a vaccine that proves efficacious by early 2021, not a certainty, it will still take the better part of a year to administer this to the vast majority of Americans - and I had been thinking that we need to reach 60% or so of the population to achieve "herd immunity" where the virus should die out. That's actually incredibly difficult!

If the SARSCoV2 virus' infectiousness, known to epidemiologists as R naught (R 0), is 2.5, meaning that each person infected spreads the disease to 2 1/2 others, then we need to achieve 60% immunity to have herd immunity. Here's a graph that shows the importance of R naught in calculating threshold for herd immunity. For context, the R 0 for measles is around 16 – so 94% need to have immunity to achieve herd immunity.

To achieve 60% immunity, we'd need to immunize 82% of those who never had COVID-19 in the past. When we remove those with severe illness, those who oppose vaccinations, and those who simply can't be reached, this sounds really hard. Calculations are in the table here.

1

R naught

R 0

2.5

2

Herd Immunity Threshhold

1-1/R 0

60%

3

Portion of population already immune from previous infection:

10%

10%

4

Additional portion needing to be immune to hit herd immunity

60%-10%=50%

50%

5

Vaccine effectiveness

75%

75%

6

Portion of total population needing vaccine

Line 4/Line 5

67%

7

Portion of those who never had infection needing vaccine

Line 6/(1-Line 3)

74%

So - why am I becoming more optimistic?

Because the infectiousness (R 0) of an infectious disease is not a fixed number. The infectiousness goes up in environments where there is more opportunity for spread (like a noisy crowded college bar), and plummets when the opportunity to spread is decreased. That's why quarantines work. If those with the disease can't interact with others in the community, it doesn't matter how contagious a disease is.

We've been trying to decrease the infectiousness of the novel coronavirus through quarantines, physical distancing, masks, and handwashing. This works - as is evidenced by end of the bad infection wave when these interventions took hold in different communities. There is no vaccine available in countries like Hong Kong and Taiwan - and they've had only scattered outbreaks, very few deaths, and have been able to (mostly) restart their economies. They've accomplished all this with these public health measures.

But it's been desperately hard in the US to quarantine those who might be infectious when tests take many days (or weeks) to return. This is a special problem since many who are infectious don't feel too badly, and some have no symptoms at all.

Furthermore, we simply can't provide enough testing if tests cost $150 each and require multimillion dollar laboratories and trained technicians, or a fancy point-of-care testing machine that is on backorder!

We've been thinking of testing as "diagnostic testing", where getting an absolutely accurate answer is critical - even if it costs a lot and takes a long time. What we need is "assurance testing," where many people, even most people, are testing themselves every day or two even if they have no symptoms. We also need to accept tests that are a lot less sensitive - but are cheap and rapid - to achieve the goal of diminishing disease prevalence to close to zero.

The Antigen tests are coming, and many researchers believe they can cost as little as $1 each and be developed at home. There are many scientists now advocating for the FDA to approve such a test. A less sensitive test that can be done often will prevent far more disease than a more sensitive test done infrequently, as I noted earlier this month.

Currently available polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests pick up 1000 viral units per ml in secretions, and the antigen tests might not turn positive until people have 100,000 viral units in their respiratory secretions. That might seem like there would be a lot of misses - but it won't matter that much if people are testing frequently. Further - these tests probably pick up those who are most contagious, and tell them to quarantine right away.

Here's what's making me more optimistic. If we can use antigen testing and distancing to diminish infectiousness (R 0) to just 1.5, we only need to vaccinate 35% of those who have not previously had an infection. If we can get the infectiousness rate down to 1.2, then we would just need to vaccinate 10% of those without previous infection to reach the herd immunity threshold. This makes it easier to be a real optimist.

We're not there yet - these tests need to be approved by the FDA and they need to be mass produced and distributed. But the combination of cheap self-service testing and vaccination could give us substantial relief sooner than I was previously thinking.

Widespread frequent testing, even with a vaccine, wouldn't necessarily mean that life would return to pre-pandemic normal. We'll likely still want to restrict large gatherings, and I would wait to go to a stadium or a bar until there were many weeks of no cases of community transmission.

We should all get comfortable with our masks, and I'm done shaking hands. But this feels to me like a dose of really good news.