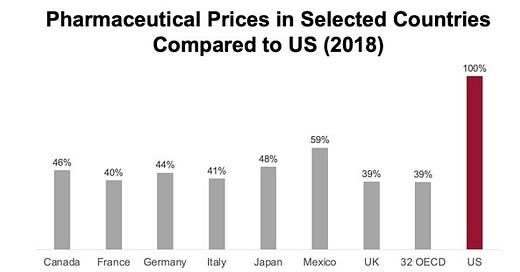

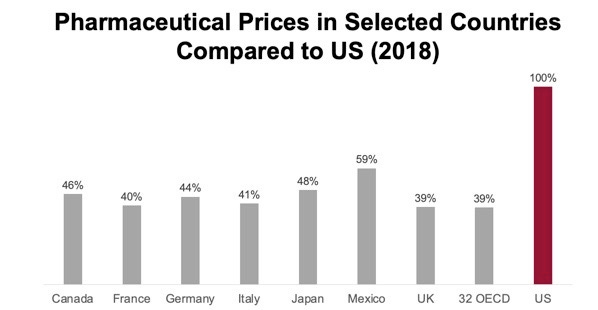

Other countries pay just 39% of what the US pays for drugs

Today’s Managing Health Care Cost Number is 39%

RAND published data on US drug prices late last month. No surprise, US drugs are the most expensive in the world. They express other country’s prices as a percent of US costs (and most are in the 250-350%; I prefer to show this with the US as the standard - so other country’s prices are uniformly less than 60% of the US prices. All of the countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development together have drug prices 39% of those in the US.

Why is this?

For starters, we are richer than other countries. Based on “purchasing power parity,” we should pay at least a bit more for drugs than other countries do - though there are a few countries now that have higher GDP per capita than the US (Norway, Switzerland, Luxembourg for instance), and so our drug prices should theoretically be a bit lower.

Most importantly, we are the only developed country that offers iron-clad patent protection to pharmaceutical companies and doesn’t either have national price-setting, a single payer system, or national negotiations. Most other developed countries also consider price when determining whether to approve new medications. The Food and Drug Administration is prohibited from doing this. Medicare, the largest purchaser of drugs, was prohibited from negotiating or setting outpatient drug prices by the law which established Medicare Part D.

There is real energy to address high drug prices - but many of the approaches that are offered are unlikely to offer sustainable decreases in overall pharmaceutical costs.

Importation.

The Trump Administration favored this- and the Health and Human Services Department for the first time said that this could be safe. Multiple states, including Colorado and Florida, are in the process of negotiating contracts for a middleman to do this importation from Canada. It’s pretty costly (Florida got no bidders when if first offered a contract!), and it seems clear that the Pharmas would not supply enough drugs for this to be sustainable if used widely. The Canadian government would likely step in to avert shortages for their citizensPrice regulation pegged to international prices.

The Pharmas say they are deeply worried about this - but game theory suggests that if we do that the result will be higher Pharma profits -because they will raise prices elsewhere to avoid having to lower prices in the US, which represents a disproportionate share of total margin. If they were not allowed to raise prices elsewhere, they would likely stop selling some high margin drugs in the reference price countries - which would lead to enormous pressure on governments to relent and grant price increases. It’s also not clear to me - if we want to regulate prices, why should we rely on other countries to do this for us?Rebates.

Legislators really like letting others do the negotiating, and OBRA 1990 granted Medicaid the “most favored nation” best prices on pharmaceuticals. Subsequent legislation has increased the rebates required for Medicaid drug acquisition. Most favored nation approaches favor the seller - and create strategic inflexibility that makes it easier for the pharmas to maintain their price discipline. Here’s a graphic from the Congressional Budget Office showing how the Medicaid MFN regulations decreased discounting for other payers from 36% pre-OBRA to 15% afterward.

Big steps, like allowing Medicare to set or negotiate rates, could clearly lower total costs - although they would be opposed by both Pharma and by the myriad of health plans that offer Medicare Part D plans. We would essentially have to nationalize that industry, and that’s never pretty.

Other steps, like “value based purchasing,” are favored by the pharmaceutical companies since it distracts policymakers from addressing the fact that many drug prices are too high. Commonwealth Fund reviewed outcome based pricing in 2017 and found that

...the power of these contracts to curb spending is questionable, largely because their applicability is restricted to a small subset of drugs and meaningful metrics to evaluate their impact are limited. There is no evidence that these contracts have resulted in less spending or better quality.

The Biden Administration is moving ahead with its COVID recovery package through reconciliation - which requires budget neutrality after ten years. Lowering the prices that the government pays for medicines would be helpful for subsequent legislation which would likely require a “paygo” to offset the costs of expanded social programs, so we’ll probably hear more about drug pricing in the coming months.