Who gets paid what in the generic drug supply chain

August 12, 2024

Source: Mattingly, et al JAMA Health Forum October 20, 2023 LINK

I took some time off, so this is a re-run of a post from last fall. I’ll be back with new posts on Friday.

Generic drugs are wonderful. Generic drugs for conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol allow us to lower the risk of a heart attack or stroke, and cost just a few dollars a month. Generic drugs must meet rigorous FDA standards to be bioequivalent to brand name drugs, and it is rare that someone clinically needs a brand name drug for which a generic is available. Generic drugs cost less in the United States than in other countries - and have helped us keep a lid on the total cost of medical care.

But since manufacturers are paid little for generic drugs, they are periodically in short supply. This is a big problem right now with drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and has also been a problem with certain generic chemotherapy medications. Generic drugs are well-reimbursed for the first year after brand name patent expiration. The first generic to market typically receives 180-day market exclusivity, but reimbursement goes down rapidly when multiple competitors enter the market. Therefore, when a generic manufacturer needs to build a new production line, they will often simply stop supplying the medication, leading to shortages.

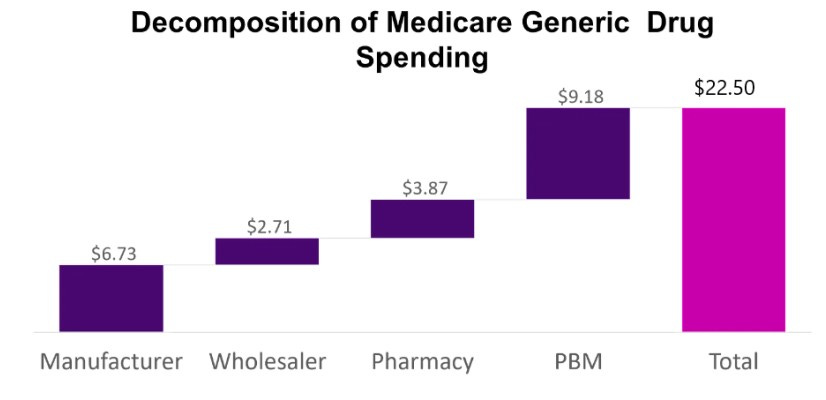

Researchers published data in JAMA Health Forum from the Medicare Part D dashboard to assess spending on 45 widely used generic medications. The average reimbursement paid was $22.50 per prescription, and the researchers deconstructed this to see how much revenue was captured by the manufacturer, and how much revenue was captured by each participant in the supply chain. As you can see, the big winner in this analysis is pharmacy benefit managers, which capture 41% of total revenue. The manufacturers capture 30% of the total spent on their medication.

Implications for employers:

- This analysis demonstrates “spread pricing,” where the PBM pays the pharmacy substantially less than it charges the insurer. This research focused on Medicare data, which is publicly available, but similar supply chain revenue capture is likely in commercial insurance.

- Generic manufacturers often need higher prices to encourage them to continue production of medications when they need to make a new capital investment.

- PBMs might be using proceeds from generic spread pricing to subsidize other activities, such as processing lower-margin specialty drugs and keeping their management fees artificially low. These funds can be shared with employers; however, this approach is non-transparent, and means that those with medical bills are overpaying to allow lower premiums for the whole population[CM1] .

- There are multiple bills currently before Congress to regulate the pharmacy supply chain. Employers should watch these carefully, as they could have a substantial impact on employer sponsored health plans.

Update - these bills did not make it through Congress this year, although there is one more chance in the lame duck session after this fall’s election.